by Nicholas Zill

Much attention has been paid to the criminal justice system in the United States and the need for reform. Yet there is a dearth of information about the well-being of children of incarcerated men and women.

We know from periodic surveys of prisoners conducted by the federal Bureau of Justice Statistics that family dysfunction is a recurring theme in the life stories of convicted criminals.1 Most men and women in federal and state prisons did not grow up in stable two-parent households. They came from single-parent families, were raised by grandmothers or aunts, or spent years in foster homes and institutions. More than half have a father, brother, or other family member who has also “done time.” And more than one-quarter had a minor child at home at the time of their arrest.2

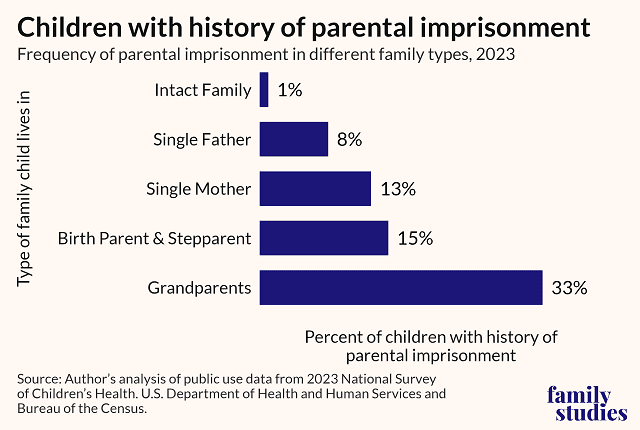

How do the children who are left at home when fathers or mothers are imprisoned function and develop? Do they show resilience in the face of separation from a cherished parent? Or do they have more than their share of learning, emotional, and behavioral problems? I analyzed data from a national survey of children’s health to get some preliminary answers to these questions.3